Street trees make up a significant portion of the urban forest. Strategically planted street trees can assist planners in goals related to transportation and public spaces.

When small parcels of land are repurposed into pocket parks with trees and seating, they augment the green infrastructure network of a city and can become spaces for social interaction.

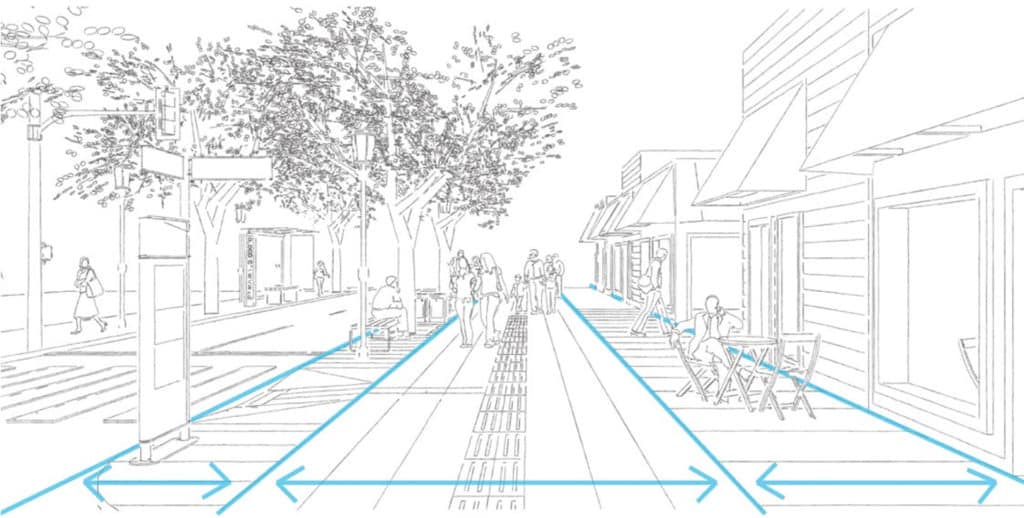

Some cities are adopting “complete streets” policies to create integrated networks of streets that facilitate safe and accessible travel for all people—regardless of age, socio-economic status, ethnicity, ability, or preferred mode of travel. (Seskin, 2013) When well-planned and well-maintained, urban forests can serve a role in the complete streets movement by reducing air temperatures, providing shade, slowing traffic, and in some instances protecting commuters from some environmental and safety hazards such as air pollutants. (McPherson, 1994; Nowak, Crane, & Stevens, 2006)

Trees can be incorporated into complete streets and transportation plans by:

- Allocating sufficient space in sidewalk design for the growth of their roots and canopy.

- Incorporating appropriately sized and placed trees as a traffic calming measure. (Wolf, 2006)

However, tree placement must be designed to avoid impeding pedestrian movement, creating obstacles for the disabled, or damaging above-and-below-ground utilities. Improperly placed or sized trees can also block drivers’ line of sight. (Wolf, 2006)

Mexico City recently implemented a complete streets design on its Avenida Eduardo Molina, including dedicated bus lanes, renovated sidewalks, and a green central median. (WRI, 2015)

The city of Medellín, Colombia is using trees and other plants to improve commuters’ conditions. To address the urban heat island (UHI) effect and promote biodiversity, the city has expanded greenspace along 18 roads and 12 waterways. To accomplish this, the city’s botanical gardens hired and trained more than 70 botanists—many of whom were from vulnerable or displaced populations. (Ashden, 2019)

More than 8,000 trees and nearly 350,000 shrubs have been planted since the program’s inception. The new trees and other vegetation reduce the temperature of the corridors by 2-3°C. More than 1 million people travel through downtown Medellín daily—either for work, for school, or as tourists. Pedestrians, cyclists, local businesses, community members and vulnerable populations alike are benefiting from the shade. (Ashden, 2019)

Please see the Selected Resources slide for more information on public space interventions.